Carl Laubin

Plus One Gallery is pleased to present a solo show of works by Carl Laubin. This follows his highly successful solo show in 2007 Verismo, based on a work from the 1490's, possibly by Luciano Laurana and now in the Palazzo Ducale in Urbino. Verismo imagined that Laurana's Ideal City had been built and the city centre had survived into the present day. For this show, Laubin turns his attention and masterful skill to the architecture of Sir John Vanbrugh.

'I decided as long ago as 1996, when I painted a capriccio of different aspects of Castle Howard and began a painting of Nicholas Hawksmoor's buildings which would take four years to complete, that at some point I would produce a painting of Sir John Vanbrugh's designs. Having painted tributes to Hawksmoor and Sir Christopher Wren, it could only be a matter of time before this third great English Baroque architect became the subject of a painting. The time finally presented itself in 2010, and the two resulting capricci, Vanbrugh Fields and Vanbrugh's Castles, depicting the majority of Vanbrugh's buildings and projects form the core of this exhibition.

Vanbrugh's interest in medieval and military architecture led naturally to compositions which grouped his designs into imagined hill towns complete with fortifications built from the bastions he designed for the landscape at Castle Howard. The approach from the beginning was to create a believable setting for these buildings, and one suitable to Vanbrugh's particularly romantic vision of architecture, rather than an artificial or abstract arrangement.

Both paintings feature Vanbrugh's bridge at Blenheim, as originally designed with the arcaded superstructure which was never built and showing the lowest storey later obscured when the water level of the valley was raised by Capability Brown. It is a structure I have painted many times before, but never so prominently in this original form. I recalled a description by John Outram of the formula for a classical landscape painting which always included a bridge in the foreground which took the viewer over a body of water into the painting. This sense of entering is reinforced in Vanbrugh Fields by including the Pyramid Gate from Castle Howard in the approach to the bridge, the pyramid symbolizing passage from one world to another.

It became apparent with very little research that much of Vanbrugh's work exists only on paper, many projects having never been built, designs altered or structures demolished for a variety of reasons including changes in architectural taste; "Lie heavy on him earth, for he hath laid many a heavy load on you". Vanbrugh Fields, andVanbrugh's Castles, depict a number of structures which do not exist today. This is where I find the greatest enjoyment in a capriccio, imagining what the drawing would be like if it were built. As with the bridge at Blenheim, Castle Howard is shown as it appears in drawings, completed symmetrically, and in Vanbrugh Fields, with the grand entrance gateways, which no longer exist, shown in front of the house as they are depicted in Vitruvius Britannicus and in a sketch by Vanbrugh. These seem to be something of a mystery, apparently having been built, as eyewitness descriptions of them exist and their footprints appeared on the ground in aerial photographs taken in the drought of 1976. Pieces of dressed stone were also discovered in recent excavations on the site of these gateways, but it is not known to what extent they were built or when they were demolished.

The demolished house at Eastbury Park is depicted as it was built and also in the form of an earlier design illustrated in Vitruvius Britannicus, complete with its grand courtyards and outbuildings reconstructed from drawings and a contemporary painting of the house. This seemed an appropriate approach to depicting a design which went through numerous alterations and developments before arriving at its final form, only to be demolished a mere half century after its completion. The demolished Great Temple and Bagnio from Eastbury are also incorporated into the landscapes of the paintings.

Perhaps the most whimsical element is the inclusion in Vanbrugh Fields of the ancient Woodstock Manor with a wisp of smoke from the chimney indicating Vanbrugh is in residence. I hope he would have approved of this as he fought unsuccessfully with the Duchess of Marlborough for the retention of this house, and the dispute, which revealed he had been staying in the manor on his visits to Woodstock and carrying out restoration work, played a significant role in the breakdown of relations with the Duchess and his departure as architect of Blenheim.

The other works included in this show can be described as distractions providing a break from the single-minded involvement demanded by the capricci. There are several paintings resulting directly from visits to Vanbrugh's buildings, but others have no relation to Vanbrugh whatsoever and were done as a diversion in the long period of production of the larger works. It was sometimes necessary in the total immersion required by the capricci to come up for air and do something completely different so a freshness of approach could be maintained when returning to the main work at hand.'

Carl Laubin, 2011

-

The Last Bastion

oil on canvas

107 x 71 cm

-

Staircase, Seaton Delaval

oil on canvas

61 x 45 cm

-

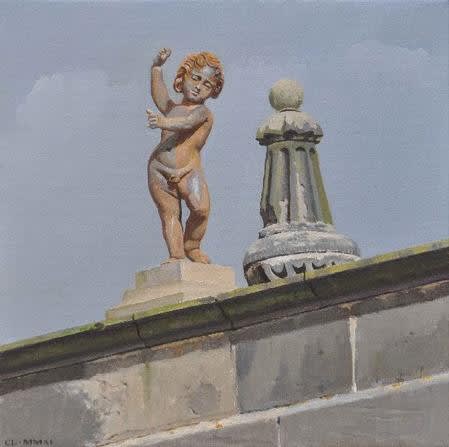

Putto, Seaton Delaval

oil on canvas

30.5 x 30.5 cm