Natural foods such as fruit and vegetables often become the subject of hyperrealist art. Berries, citrus fruits and other varieties are put under a microscope and blown up to create monumental, bold and indulgent paintings that celebrate life.

The brightly coloured, incredibly detailed blown up renditions of fruit successfully approach a very traditional format, still life, in perhaps a more contemporary way – minimal in form yet very complicated in process.

Still Life is one of the principal genres of Western art and uses a range of man-made or natural objects including fruits, vegetables, flowers and game as subjects. This style of painting can be a celebration of material pleasures or a warning of the ephemerality of these luxuries and the brevity of human life.

Using still objects as a subject in art is something that spans the centuries and there has been surprisingly little change in the type of objects used. However, the way these objects are depicted has changed, reflecting developments in style and technique.

Many hyperrealists explore fruit as a representation of mortality and the transient nature of our existence. When the fruit is portrayed as being fresh and ripe, this signifies abundance, fertility, youth and vitality. However, decaying fruit serves a reminder of undeniable mortality and the inevitability of change.

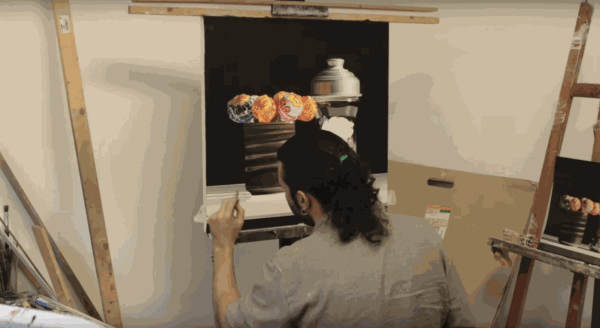

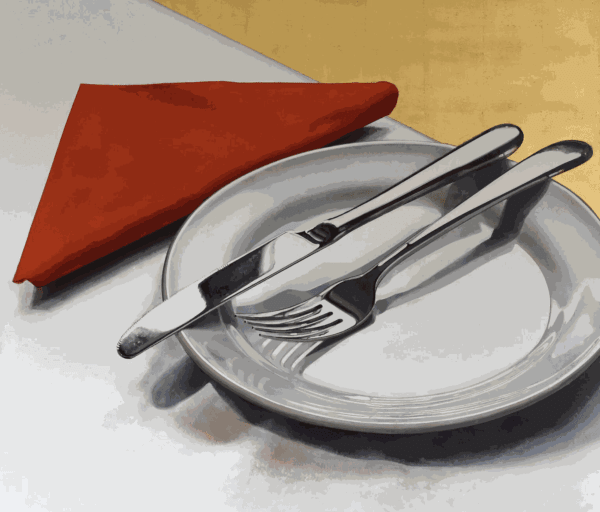

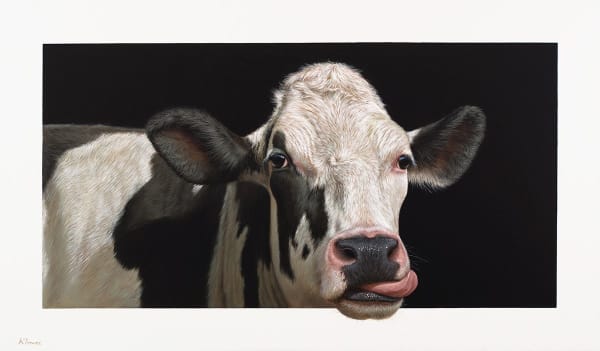

Red by Tom Martin

History

Rather than being a contemporary phenomenon, the depiction of fruit in art dates back to the Ancient Egyptians. Paintings of food were added to the tombs of Pharaohs under the belief that, in the afterlife, the deceased would be able to feed on the depicted food.

The 16th century discoveries of the New World and Asia intensified interest in the exotic and unusual. The fascination was recorded visually in still life paintings featuring an array of exotic fruits and botanicals.

In “Still Life: A History”, Sybille Ebert Schifferer suggests that depictions of fruit in 16th-century art act as symbols of the seasons and of the senses. She also alludes that while the still life paintings of the era presented a representation of upper class delicacies on the surface, a religious undercurrent reminding the viewer to avoid gluttony and excess is also present.

The traditional style of 16th century Still Life paintings still exists today, albeit with a thoroughly modern sensibility and exquisite sense of form and composition. This traditional style is visible in the work of James Del Grosso, who uses light to reveal the solidity of his forms and the clarity of his meticulous application of glaze upon glaze. However, his use of vibrant hues closely follows the hyperrealist way of breathing life and vitality into subjects using colour.

Hands Creek Apple by James Del Grosso

Colour

In many of his paintings, Spanish hyperrealist Antonio Castello often depicts fruits at the peak of ripeness. By gathering varieties of fruits and enlarging them to fill either part of or the whole canvas, Castello creates a kind of landscape out of food, generating a significant sense of monumentality. He uses vivid colours which invigorate his subjects and breathe life and vitality into each composition. For instance, in ‘Raspberries’ his tantalising use of red gives the berries a succulent appearance.

Raspberries by Antonio Castello

Similarly, Ben Schonzeit covers the whole of the canvas with a mass of fruit. In ‘Lady Apples’ and ‘Tart’ we see an almost abstract style composition which focuses on a section of a group of fruit. The contrast in colour between the punchy red and the mellow cream in ‘Lady Apples’ reveals a realistic ripeness like no other. The techniques Schonzeit uses to create the reflective quality on the ‘Tart’ add to the bold blueberries and bright peaches.

Tart by Ben Schonzeit

Representation

By exploring natural food at its most fragile, artwork becomes transitional. Hyperrealists often invigorate fruits with colours that denote flavour and vitality, but away from the canvas, the exuberance of ripe fruit ultimately fades as it ages and decays – much like the human life cycle. Antonio Castello gives evidence of decay in “Grapes III”.

The use of decaying fruit in hyperrealism harks back to the Vanitas themes of the 16th and 17th century, where solemn still lifes of skulls, wilting flowers and decaying fruit interplayed between life and death. The morbid Vanitas style of painting translates to “emptiness” in Latin, and intended to evoke the transient nature of earthly life and vanity.

Humans and food

Fruit, unless growing naturally in the wild, is cultivated for human consumption. We need food to survive and therefore have a considerable relationship with the produce we grow. Many hyperrealists incorporate the presence of humans into their still life paintings to explore our relationship with food and examine survival in consumerist society.

Jacques Bodin portrays fruit at the point of purchase. In “Fruits XX”, Bodin depicts oranges that have been pre-packed by a supermarket or greengrocers and will inevitably go on to be consumed.

Fruits XX by Jacques Bodin

In contrast, Elena Molinari and Cynthia Poole paint fruit after purchase and add domestic equipment, pottery and ornate vases to their paintings, fusing man-made objects with natural produce. The coexistence of natural and synthetic, such as oranges, pottery and metal cutlery in “Outspan #4450”, explore the relationship between the perishable and the non-perishable. The orange rind featured in the painting completes a cycle of human consumerism – purchase, storage and ultimately consumption.

Outspan #4450 by Cynthia Poole

Eight Figs by Elena Molinari

Moving away from using fruit in its pure form for still life portraiture, these artists incorporate human interaction that denotes a passing of time. Just as one artist would paint fruit at peak ripeness, these artists paint food in a period of transition, from the tree to the table, from the table to the mouth. The difference being that the subjects of his paintings are inanimate, therefore they are not suspended in life but instead are captured in action.

Related artists

- Tumblr

Add a comment

-

-

Blog entries

Blog entriesHyperrealism Today

Article on Hyperrealism written by Maggie Bollaert published on EF Magazine -

Blog entries

Blog entries7 Questions for Plus One Gallery Founder Maggie Bollaert on Why She’s Heralding the Next Generation of Hyperrealist Artists - Artnet Article

The London-based gallery has championed contemporary figurative art since 2001 -

Blog entries

Blog entriesArtist in Focus - Mike Francis

1938 - 2023 -

Blog entries

Blog entriesJohannes Wessmark for American Art Collector

-

Blog entries

Blog entriesMeet the Photorealists

-

Blog entries

Blog entriesCarl Laubin - Homage to Le Corbusier’s Pessac

-

Blog entries

Blog entriesArtist in Focus: Ben Johnson

-

Blog entries

Blog entriesGet Ready for Christmas with the Perfect Stocking Fillers

-

Blog entries

Blog entriesArtist in Focus: Paul Beliveau

-

Blog entries

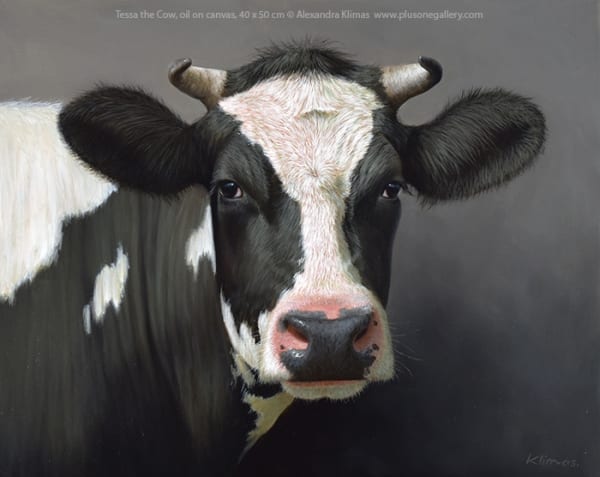

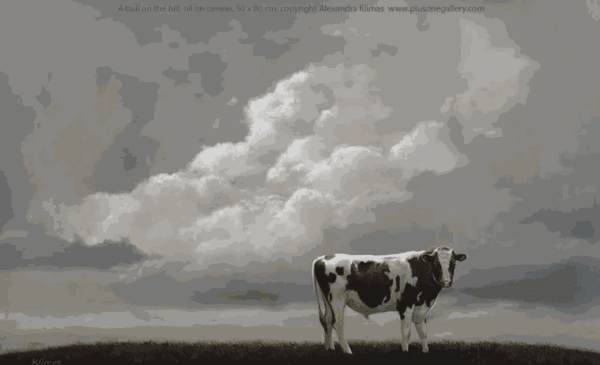

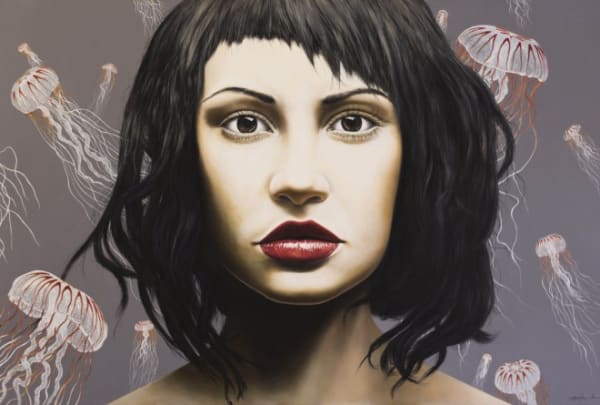

Blog entriesAlexandra Klimas in Landleven Magazine

Alexandra Klimas paints in tribute to the animal -

Blog entries

Blog entriesPOG's Christmas Suggestions

-

Blog entries

Blog entriesHAPPY ANNIVERSARY PLUS ONE GALLERY

September 2001 - September 2021 -

Blog entries

Blog entriesArtist in Focus: David Kessler

-

Blog entries

Blog entriesArtist in Focus: Sergey Piskunov

-

Blog entries

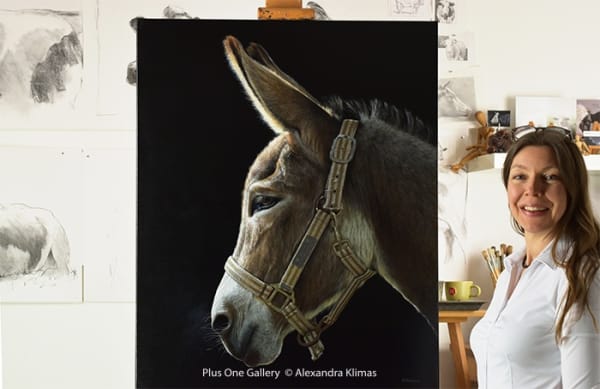

Blog entriesArtist in Focus: Alexandra Klimas

-

Blog entries

Blog entriesLet's Get Ready for Christmas! - Volker Kuhn

November 30, 2020 -

Blog entries

Blog entriesArtist in Focus: John Salt

-

Blog entries

Blog entriesFeel Like We’re Living in Surreal Times?

Let These 5 Leading Hyperrealist Artists Ground You -

Blog entries

Blog entriesAn Interview with Maggie Bollaert

For www.hyperrealism.net -

Blog entries

Blog entriesArtist in Focus: Andres Castellanos

-

Blog entries

Blog entriesThe Story Behind the Painting II: Alexandra Klimas

Hope the Donkey -

Blog entries

Blog entriesCarl Laubin: Elegos

World Trade Centre – Ground Zero -

Blog entries

Blog entriesAll You Need is Love!

-

Blog entries

Blog entriesOur December Winter Picks

The ultimate cozy artworks for your living room this winter -

Blog entries

Blog entriesArtist in Focus: Adolfo Bigioni

-

Blog entries

Blog entriesThe Story Behind the Painting I: Denis Ryan

-

Blog entries

Blog entriesArtist in Focus: Young-sung Kim

-

Blog entries

Blog entriesHiperrealisme | 21 Jun - 30 Sept | Museu del Tabac, Andorra

-

Blog entries

Blog entriesPlus One Gallery, The Piper Building

-

Blog entries

Blog entriesHyperrealism: Resources for the Artist

-

Blog entries

Blog entriesHappy Mother's Day!

She's looked after you all this time, make sure she knows she special! -

Blog entries

Blog entriesWinter Show

January 17, 2018 -

Blog entries

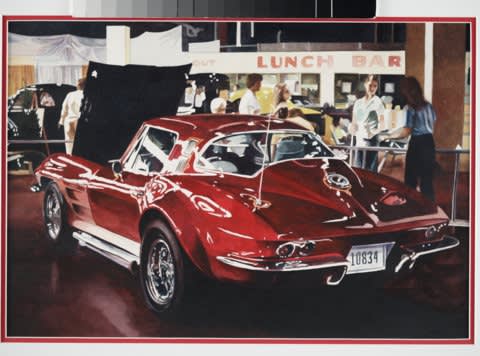

Blog entriesPhotorealism of the 1960s

January 10, 2018 -

Blog entries

Blog entriesThe tradition of still life

November 29, 2017 -

Blog entries

Blog entriesArtist in Focus: Javier Banegas

November 15, 2017 -

Blog entries

Blog entriesArtist in Focus: Tom Betts

November 13, 2017 -

Blog entries

Blog entriesJavier Banegas Private View

-

Blog entries

Blog entriesNovember News

November 1, 2017 -

Blog entries

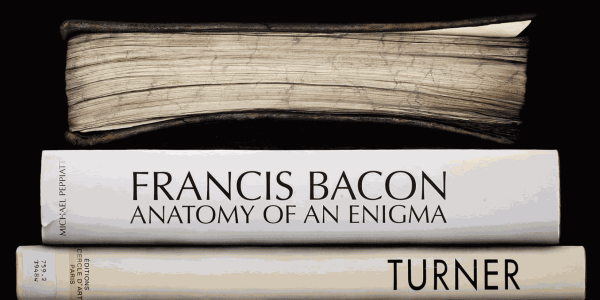

Blog entriesArtist in Focus: Paul Beliveau

October 25, 2017 -

Blog entries

Blog entriesYOUNG-SUNG KIM

October 18, 2017 -

Blog entries

Blog entriesSeptember News

September 12, 2017 -

Blog entries

Blog entriesArtist in Focus: David Kessler

-

Blog entries

Blog entriesGallery News!

Simon Hennessey wins the acrylic paint category of the Jackson Painting prize 2017 -

Blog entries

Blog entriesArtist in Focus: Paul Cadden

August 10, 2017 -

Blog entries

Blog entriesArtist in Focus: Simon Harling

August 4, 2017 -

Blog entries

Blog entriesArtist in Focus: Javier Banegas

July 21, 2017 -

Blog entries

Blog entriesArtist in Focus: Francois Chartier

July 10, 2017 -

Blog entries

Blog entriesAn Interview with Christian Marsh

June 21, 2017 -

Blog entries

Blog entriesSummer Picks at Plus One Gallery

June 7, 2017 -

Blog entries

Blog entriesPRIVATE VIEW

Tom Martin: Perpetual Motion May 17, 2017 -

Blog entries

Blog entriesArtist in Focus: Andres Castellanos

-

Blog entries

Blog entriesArtist in Focus: Steve Whitehead

-

Blog entries

Blog entriesGallery News!

Carl Laubin is announced as the Winner of the 2017 Arthur Ross Awards for Excellence in the Classical Tradition, in te Fine Art Category. -

Blog entries

Blog entriesWorks to Watch

Angus McEwan April 10, 2017 -

Blog entries

Blog entriesPrivate View

Cynthia Poole: Gold Pieces & other Explorations -

Blog entries

Blog entriesAn Interview with Cynthia Poole

March 30, 2017 -

Blog entries

Blog entriesTom Martin : Sculptural Works

May 31, 2017 -

Blog entries

Blog entriesAn Interview with Tom Martin

May 24, 2017 -

Blog entries

Blog entriesArtist in Focus: Cynthina Poole

March 22, 2017 -

Blog entries

Blog entriesArtist in Focus: Denis Ryan

-

Blog entries

Blog entriesAn Interview with David Finnigan

-

Blog entries

Blog entriesSpring Picks at Plus One Gallery

-

Blog entries

Blog entriesArtist in Focus: Simon Hennessey

-

Blog entries

Blog entriesPlus One Gallery's Top 5 picks this month

-

Blog entries

Blog entriesWinter Show Private View

-

Blog entries

Blog entriesWinter Show: Artists

An Interview with David Wheeler -

Blog entries

Blog entriesWinter Show: Artists

An Interview with JKB Fletcher -

Blog entries

Blog entriesWinter Show

-

Blog entries

Blog entriesMERRY CHRISTMAS

from everyone here at Plus One gallery: Maggie, Colin, Rosie, Scarlett and Archie -

Blog entries

Blog entriesA Sentimental Journey

Carl Laubin's journey in the creation of his solo show -

Blog entries

Blog entriesNew destination on the Grand Tour

RIBA J article written by Hugh Pearman -

Blog entries

Blog entriesAn Interview with Carl Laubin

November 30, 2016 -

Blog entries

Blog entriesCarl Laubin: A Sentimental Journey Private View

With guest speaker Prof. Adrian von Buttlar -

Blog entries

Blog entriesCountdown to the Carl Laubin Show!

Carl Laubin: A Sentimental Journey -

Blog entries

Blog entriesNovember News

-

Blog entries

Blog entriesElena Molinari Interview

Exhibition 'The Alchemy of the Everyday' runs until 19th November November 2nd 2016 -

Blog entries

Blog entriesPrivate View: Elena Molinari: The Alchemy of the Everyday

-

Blog entries

Blog entriesElena Molinari: The Alchemy of the Everyday

Invitation -

Blog entries

Blog entriesElena Molinari: The Alchemy of the Everyday

October 7, 2016 Plus One Gallery is delighted to announce 'The Alchemy of the Everyday', the forthcoming solo show by Uruguayan gallery artist Elena Molinari. -

Blog entries

Blog entriesWhat's New This October

October 4, 2016 It has been an exciting year so far and it doesn't look to be slowing down with some fabulous new works from the likes of Alexandra Klimas, Pedro Campos and Roger Watt. -

Blog entries

Blog entriesAn Interview with Tom Martin

October 12, 2016 Plus One Gallery catches up with hyperrealist Tom Martin to discuss his creative process and why he is keen to distance himself from the restraints of a digital camera. -

Blog entries

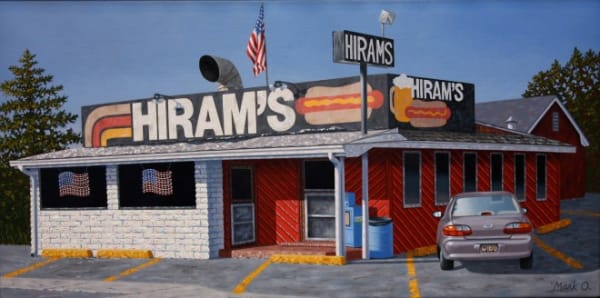

Blog entriesReinterpreting the American Dream in hyperrealism

October 5, 2016 -

Blog entries

Blog entriesPlus One Gallery Official Opening Show

September 22, 2016 -

Blog entries

Blog entriesOpening Show: Battersea Reach

September 15, 2016 We are excited to launch the opening show at our new premises in Battersea Reach where a range of exquisite hyperrealist art will be on display. -

Blog entries

Blog entriesA trip down memory lane: Nostalgia in hyperrealism

September 8, 2016 Plus One Gallery examines nostalgia and hyperrealism, looking at vintage iconography, items and period images rendered in hyperrealistic art. -

Blog entries

Blog entriesNew Artists: New Space

September 1, 2016 With the launch of our new premises at Battersea Reach, we are delighted to unveil the work of some of our latest artists. -

Blog entries

Blog entriesAn interview with Christian Marsh

-

Blog entries

Blog entriesArtist in Focus: Thomas Ostenberg

August 25, 2016 A closer look at the work of Thomas Ostenberg, whose sculptures explore the theme of motion and balance, reflecting his personal search for emotional equilibrium. -

Blog entries

Blog entriesHow to find us at our new premises in Battersea Reach

August 17, 2016 To find Plus One Gallery, please follow these instructions and travel directions. -

Blog entries

Blog entriesSunshine and seasides: Summer in all of its glory

August 10, 2016 The summer months breathe new life into the canvases of hyperrealists, as flowers come into full bloom and coastlines shimmer in the unwavering sunlight. -

Blog entries

Blog entriesREMINDER: SUMMER SHOW PRIVATE VIEW

Tuesday 19th July, 6pm-8pm July 14, 2016 -

Blog entries

Blog entriesHow is consumerist culture represented in hyperrealism?

June 29, 2016 Built around imagery of recognisable brands, celebrity cults and everyday life, consumerist art is rooted in the present social context. -

Blog entries

Blog entriesPlus One Gallery Summer Show

June 27, 2016 -

Blog entries

Blog entriesRelocation to Battersea Reach

June 23, 2016 -

Blog entries

Blog entriesArtist in Focus: David Finnigan

June 22, 2016 British hyperrealist David Finnigan aims to present a style of realism that is both a progressive and experimental development of that genre. -

Blog entries

Blog entriesAn interview with Elena Molinari

June 15, 2016 Born in Montevideo, Elena Molinari is best known for her still life paintings of fruit and vegetables, often placed in fruit bowls or alongside glass vases and silk cloths. -

Blog entries

Blog entriesSweet temptation in Hyperrealism

June 9, 2016 Using a sensuous palette of colours and textures, many hyperrealist artists explore temptation, primal pleasures and how food can comfort the soul. -

Blog entries

Blog entriesAn interview with Nourine Hammad

June 1, 2016 Plus One Gallery interviews hyperrealist artist Nourine Hammad about her unique artistic expression and process. -

Blog entries

Blog entriesIn full bloom: flowers and their role in hyperrealism

May 25, 2016 Hyperrealists are refreshing the still life genre, invigorating paintings of flowers with contemporary techniques that challenge notions of tradition. -

Blog entries

Blog entriesArtist in Focus: Craig Wylie

May 20, 2016 Craig Wylie has developed a multi-faceted but singular approach to hyperrealism that seizes the appearance of his subjects with tremendous fluency and ease. -

Blog entries

Blog entriesGallery News: We are relocating!

May 17, 2016 -

Blog entries

Blog entriesWhy painting maintains a significant role in a world of instant images

May 11, 2016 In a world where high-tech photography and instant photo messaging is available at our fingertips, what does hyperrealism give us that photography cannot? -

Blog entries

Blog entriesA taste of your five-a-day in hyperrealism

April 27, 2016 Many hyperrealists explore fruit as a representation the transient nature of life, using colour to remind us of the inevitability of mortality and change. -

Blog entries

Blog entriesThe influence of pop art in hyperrealism

April 13, 2016 Hyperrealism is often considered an advancement of Pop Art and Photorealism and first came to prominence at the turn of the millennium. -

Blog entries

Blog entriesGALLERY NEWS: We are relocating!

April 7, 2016 -

Blog entries

Blog entriesArtist in Focus: Mike Francis

Combining hyperrealism and commercial illustration April 6, 2016 Mike Francis is a photo realist, with a profoundly contemporary imagination, however his technique is deeply rooted in the Old Masters. -

Blog entries

Blog entriesArtist in Focus: Christian Marsh

Humane landscape hyperrealism March 30, 2016 Christian Marsh's body of work consists of large scale paintings, which explore composite views of various cities around the world. -

Blog entries

Blog entriesThe hyperrealist travel guide

March 28, 2016 Urban hyperrealism takes the modern metropolis as its subject. It challenges the artist to explore hidden meanings and diversity deeply rooted in society. -

Blog entries

Blog entriesArtist in Focus: Young-Sung Kim

Challenging society's materialism March 16, 2016 Young-Sung Kim produces hyperreal paintings of contrasting subject matters to illustrate the differences between the living and the material. -

Blog entries

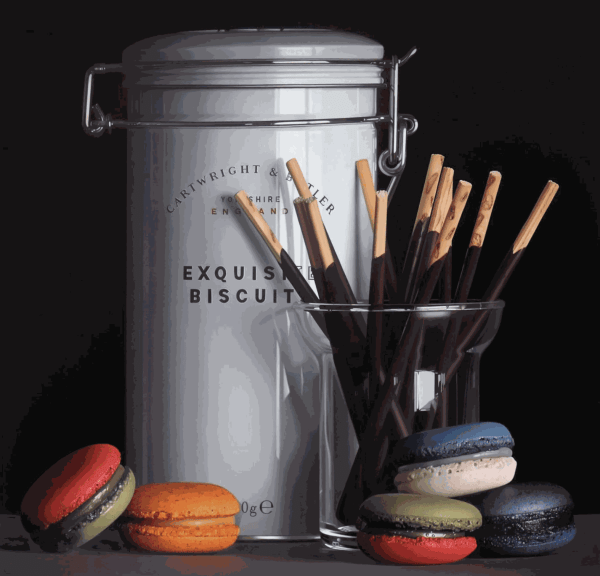

Blog entriesArtist in Focus: Cynthia Poole

Examining consumerism with nostalgia March 9, 2016 Cynthia Poole’s paintings take food packaging, sweet wrappers and chocolate bars as their subject matter; often with a warm nostalgia for the 1980s confectionery. -

Blog entries

Blog entriesMother's Day

-

Blog entries

Blog entriesIs there a place for artistic interpretation in hyperrealistic art?

January 12, 2016 -

Blog entries

Blog entriesHow does the use of photoshop affect hyperrealistic art?

December 16, 2015 -

Blog entries

Blog entriesThe difference between Photorealism and Hyperrealism

November 25, 2015 -

Blog entries

Blog entriesFive of the best hyperrealists on Instagram

November 4, 2015 -

Blog entries

Blog entriesNew media being used for hyperrealism

Plus One Gallery explores the new media being used within hyperrealism pieces. -

Blog entries

Blog entriesCities in Real Life: Urban Hyperrealism

Plus One Gallery examines the impact of street culture, through urban art, and its effect on artistic expression within hyper realism pieces. -

Blog entries

Blog entriesA Brief History of Hyperrealism

August 7, 2015 Plus One Gallery recaps Hyperrealism with a brief look at the historical influences and movements that led to modern day hyper realistic art.

-